Does Having Children Harm the Environment?

What science, ethics, and activism reveal about the impact of expanding the family on Earth’s future.

In recent years, many politicians have promoted the idea of having kids in their campaigns. Countries like Italy or Japan, for instance, encourage young families to have kids to fight the problem of an aging population. While children are the solution to restoring youth, they are also one more problem for the environment. You might wonder how a newborn can already be part of the environmental discourse and how they can threaten the environment. Well, it’s all about the demographic impact that the baby will have in the future.

On average, a human being produces 4 tons of CO2, and in some countries, such as the US, the average goes up to 16 tons of CO2. The average carbon footprint is calculated on a per capita basis, which measures the total greenhouse gas emissions generated by an individual's activities. Therefore, our carbon footprint strongly depends on our everyday choices, which means that the individualistic decision of having a child has an impact, a big one, on the general CO2 emission.

A Study Says One Less Child Could Make The Difference

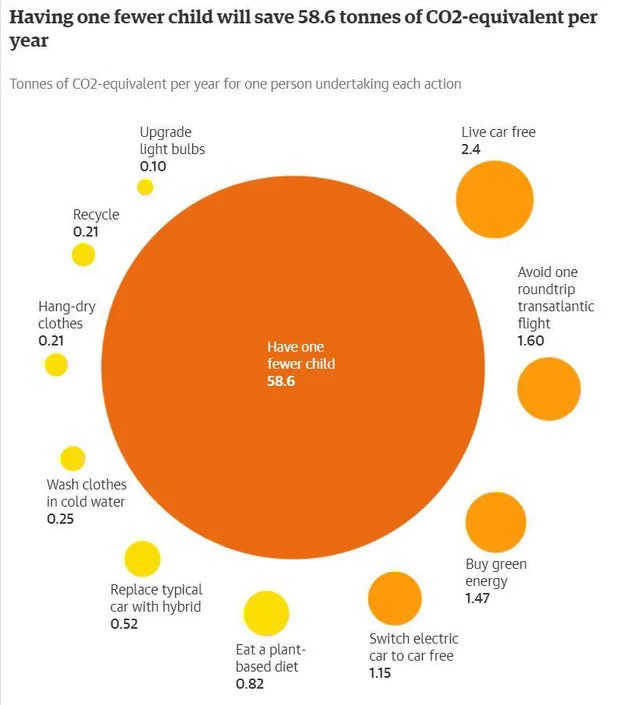

A study made by Seth Wynes and Kimberly A. Nicholas in 2017 shows how having fewer children could save up to 58 tons of CO2. The study is based on the assumption that the child will live a common lifestyle in a developed country and that their descendants will too. Therefore, each parent is being held “responsible” for half of the child’s emissions, a quarter of each grandchild’s emissions, and so on. In simple words, the study explains how if you don’t have that child, you are also stopping the pollution from the future generations that would descend from the child.

It is important to keep in mind that the study wants in no way to blame the personal choice of having a child, or multiple, it just aims to show the cumulative, long-term effects of population growth on climate. Nevertheless, the number got out of the study is a significant amount of CO2.

Another highlight that stands out in the study is how much less of an impact actions promoted as necessary for the reduction of individuals’ carbon footprint have, when compared to having a child. For instance, it is well-known that the meat industry has a huge impact on the environment and its pollution. Therefore, someone who decides to follow a plant-based diet is helping the environment quite a lot. Well, when compared with having a child, following a meatless diet looks like one is remembering to turn off the water of the sink when brushing their teeth.

Following a plant-based diet saves up to 2 tons of CO2 per person per year, and driving an electric car can save between 1 to 2 tons of CO2 per person per year. These values, when compared with the 58 tons saved by the decision not to have a child, are quite low; they almost look insignificant. The truth is that it is hard to compare these actions.

Firstly, they measure the savings of emissions on different levels, for instance, the time frame dimension. Deciding not to have a child is a once-in-a-lifetime decision that will affect generations to come, while following a meatless diet or choosing which car to drive is a decision that will help reduce your carbon footprint every year. Therefore, choosing to have one fewer child is a population-level choice, which will affect not just the individual’s emissions but also those of future generations.

The Ethics of Limiting Births for the Planet’s Sake

One could say that we have found the solution to slow down inevitable disasters provoked by climate change. Like every complex problem, the answer can never be yes or no. There are so many nuances to consider in this theme, like the ethical one or the economic contributions a new child brings to a society.

Reproductive choices are probably the main critical point of this discussion. These are deeply personal and often influenced by culture, values, and circumstances. In short, individuals cannot be limited in their personal choices of pursuing the desire of a family with a child… Or can they?

In 1979, China introduced the “one-child” policy to slow down the rapid population growth. At the time, the country’s population was going to hit 1 billion people, and the leaders feared that the excessive number of people would harm the ongoing economic development as well as strain resources. The policy limited families to one child, especially in cities. As always, exceptions were made, specifically for rural families and ethnic minorities.

The policy worked so well that in later years, China suffered from a lack of young people and an increasingly older population. In 2015, the government set the limit to two children, and recently, the limits on the number of children have been lifted. Needless to say, this policy raised major concerns about the limitation of the freedom of individuals from the government. In addition, the policy created imbalances in the population. In fact, culturally, the male figure is preferred, and this has led to sex-selective abortions, abandonment, and even infanticide of baby girls. These were only a few of the problems caused by the consequences of a restrictive and controlling policy on natality.

If overpopulation was the problem to solve in China, in countries like Italy, for instance, there is the opposite concern. Recent data show that most of the families are composed of only one young adult, and that Italy has one of the oldest populations, if not the oldest, in Europe. These data are quite concerning, especially from a socio-economic perspective. As more people retire and fewer young people enter the job market, there are not enough workers to support the economy, pay taxes, and therefore pay pensions. It is estimated that by 2050, Italy could have almost as many elderly as working-age people, doubling the financial and social pressure on younger generations.

The outcome is clear: fewer consumers and workers also means less innovation, less productivity, and therefore less economic growth. If this is already a tangible emergency, why are there few incentives to have a child? The answer is not connected to environmental concerns, but is rather related to the cost of having a child. Nowadays, raising a child in Italy costs families one-third of the average family income. It is definitely a good amount of money and something that younger generations keep in mind, especially with the salary stagnation and the precariousness of jobs, two problems, unfortunately, deeply rooted in Italy. On a positive note, following the reasoning of the study conducted by Seth Wynes and Kimberly A. Nicholas, a population that has fewer children is somehow directly contributing to the decrease in CO2 emissions.

Ecofeminism: Gender Discourse and Environmental Justice

There is one more narrative that I believe is essential to mention in this article. I’m talking about the one perpetuated by ecofeminism. Ecofeminism is the idea of thinking where the environmental and gender discourse intersect. It mainly argues that the way society treats women and the way it treats nature are linked, both rooted in systems of domination and control, such as patriarchy and capitalism.

In Ecofeminism, maternity is seen differently depending on the critique chosen to analyze. Often, the promoted narrative follows the ethic of care, which prioritizes nurturing and responsibility toward both people and planet, instead of constantly seeking profit and power. Nevertheless, this view is criticized by, for instance, the essentialism narrative, that is to say, feminists who believe the continuous equalization of women with nature and motherhood reinforces a traditional, patriarchal role over women.

Some ecofeminist thinkers, such as Françoise d’Eaubonne, have linked pronatalism to environmental justice and consequently founded a movement called Birthstrike. This one is a movement where individuals, for the majority women, publicly declare their refusal to have children due to the severity of the ecological crisis. Followers of the movement manifest their right to make decisions about childbirth in the face of environmental collapse, challenging societal expectations around reproduction. Birthstrike questions the prioritization of increasing birth rates over the well-being of parents, their children, and the environment, aligning with ecofeminist critiques of how reproductive labor is valued in patriarchal societies.

The Future of Parenthood in a Warming World

Over a long time, the number of people on Earth will affect how much CO2 emissions it is released. The decision to have a child is becoming more than just an individual decision that will shape the course of a few lives, but rather one that will eventually have an impact on the overall population. In fact, some studies have shown that perhaps having fewer children could be a turning point in the objective of lowering CO2 emissions.

Nevertheless, reproductive choices are deeply personal and, in some cases, influenced by cultural and economic factors. Some states, such as China, have successfully managed to control the reproductive rights throughout much criticized policies; however, that resulted in consequences that deeply affected the population, especially its psychological well-being. Other countries, such as Italy, are not in the position to impose limits on their citizens’ reproductive choices, and actually, an increase in the population seems like a necessary step to resolve incoming economic imbalances between the old and young.

While some worry about the economic implications of newborns, others harshly critique this capitalistic view. Some branches of the ecofeminism discourse frame reproductive autonomy and the decision not to have children as a form of resistance to both environmental degradation and the patriarchal societal expectations around motherhood. The BirthStrike movement, for instance, criticizes pronatalist policies, urging a change both in the care for the environment and for motherhood.

While it is essential to always respect individuals’ reproductive choices, as a young woman I have a question that lives rent free in my head: is it a selfish decision to want a baby knowing that they will contribute to the advancement of climate change and that they will live in a world that is destined to suffer a climate collapse?